For years, the air show community has teetered on the brink of moving to the proverbial “next level.” Even accounting for the possibility that people from within the industry may not be objective enough to make that assessment, our business appears to have most of the important pieces in place: uniquely entertaining and exciting, enormously popular, family-oriented, safe for spectators, and well-established.

But the search for the catalyst that will provide this last, little push to that next level has been elusive. From sponsorship and television coverage to air show aerobatic competitions and outside-the-industry investors, promising solutions have invariably disappointed. Our business has survived, in some cases, thrived, but always with a sense that we’re one small step away from a big industry leap forward.

As the industry continues to look for that on-ramp to the next level, we often operate with insufficient revenue to do the things we know we need to do to make our events more entertaining, better attended and stronger financially. But we also know that we must wait to make that jump to the next level to achieve that desired level of financial stability.

Or do we?

Might it be that improved financial stability is within our reach right now? Is it possible that, like Dorothy and her ruby red slippers, we’ve always had the power we need to solve this longstanding riddle?

2016 Ticket Pricing and Policy Survey Results

In February of this year, ICAS conducted a survey of North American event organizers on issues related to ticket pricing and policy. Nearly 100 ICAS members from the U.S. and Canada responded to 22 different questions.

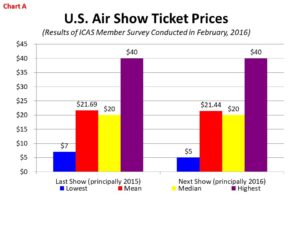

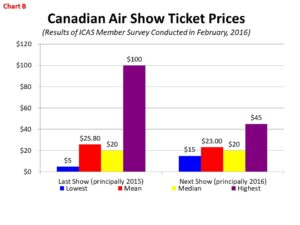

Their responses tell us that, in the United States (see Chart A), the mean ticket price in 2015 was $21.69 and the median was $20. (To ensure a consistent standard, unless otherwise noted, all ticket prices are based on an adult, on-site, non-discounted ticket.) The least expensive ticket last year was $7; the most expensive was $40. In Canada, the mean was $25.80 and median was $20 with a range of $5 to $100 (see Chart B).

In both the U.S. and Canada, organizers tell us that ticket prices will decrease slightly in 2016 as compared to 2015. In the U.S, the decrease will be 25 cents per ticket or about one percent to $21.44. In Canada, that decrease is expected to be larger: $2.80/10.8% to $23.00, although this figure is impacted by the small number of survey responses from Canadian members and one particularly high ticket price in 2015 that will not be offered in 2016.

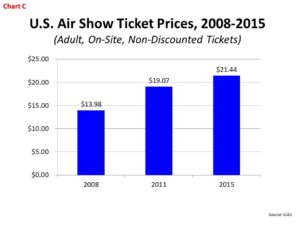

The mean U.S. ticket price of $21.44 in 2015 is another significant increase in average air show ticket prices in the U.S. (see Chart C). When ICAS surveyed its members at the beginning of 2008, the average cost of admission was $13.98. Three years later, the average had increased by 36 percent to $19.07. The $2.37/12.4% increase in average ticket price between 2011 and 2015 is smaller, but still represents a significant increase both in dollars and as a percentage.

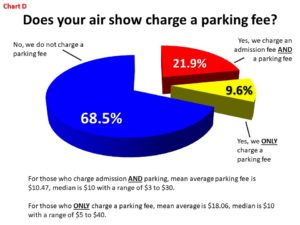

For the first time in our ticket price survey, ICAS also queried members on issues related to ticketing policy (see Chart D). Although more than two-thirds of survey respondents do not charge any fee for parking, 31.5 percent do. For those shows that have both individual admission and parking fees, the mean fee is $10.47 per vehicle and the median is $10 with a range of $3 to $30. For those shows that only charge a parking fee, the mean is $18.06 and the median is $10 with a range of $5 to $40. (Note: due to the small number of Canadian shows that charge any type of parking fee, the data was deemed to be insufficient to publish averages.)

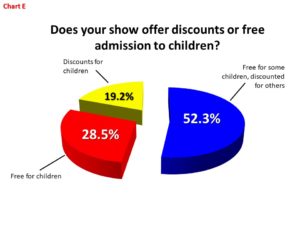

We also asked our shows to share information regarding discounts and free admission for children (see Chart E). Historically, free admission for children has been used as both a tool to engage children in aviation and a tactic to entice parents to buy tickets themselves. Among survey respondents, all events offer either a discount or free admission for children. More than half (52.3%) offer both. The circumstances under which free admission and discounts are offered to children vary considerably. For instance, although 28.5 percent of shows offer free admission to children under a certain age, about one quarter of those shows require that the child be accompanied by a paying adult. In other cases, children below a certain age are admitted at no charge and older children are offered a discount.

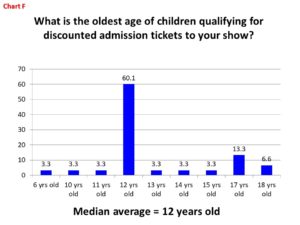

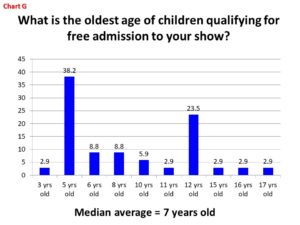

What are the age limits for discounts and free admission for children? For discounts, the range was six to 18 years old, but more than half the shows responding told us that the maximum age of children receiving discounts is twelve (see Chart F). When we asked about free admission, the results were not as definitive. Maximum ages for children receiving free admission ranged from three to 17, with the most common cut-off points coming at five and twelve. The median age for free admission was seven (see Chart G).

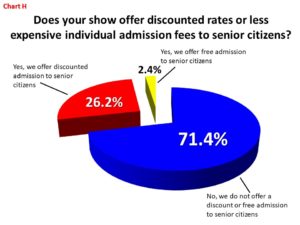

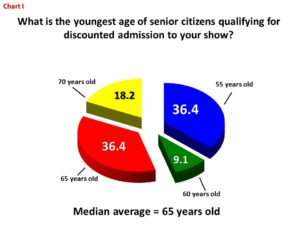

Event organizers also shared with us information about their policies on senior citizens. Nearly three-quarters (71.4%) offer neither discounts nor free admission with 26.2percent offering a discount and just 2.4percent offering free admission (see Chart H). Of those shows that offer discounts to senior citizens, the cut-off ranges from 55 to 70 with the median at 65 (see Chart I).

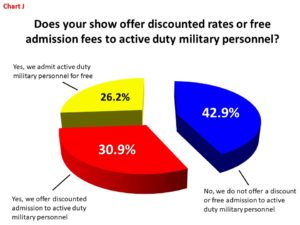

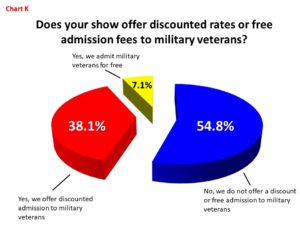

More shows offer discounts to active duty military personnel (see Chart J). About one quarter (26.2%) offer free admission to military personnel. Another 30.9 percent offer discounts to active duty military. Veterans also receive accommodations from many shows (see Chart K). Nearly two in five (38.1%) offer discounts to veterans.

My Perspective: Increase Your Ticket Prices

Our business has a revenue problem. Longstanding financial pressure has prompted many show organizers to cut expenses mercilessly. But, after years of watching this phenomenon, I’ve reached a different conclusion. The problem is not that our events are too expensive to stage; the challenge is that we are not generating enough money and, specifically, not enough ticket revenue.

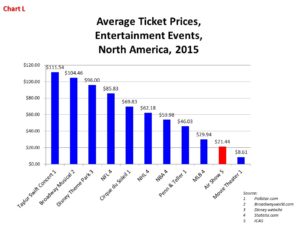

Perhaps the most compelling argument that ticket prices are too low is the admission prices of other entertainment events throughout North America (see Chart L). You’ve seen this chart or a variation of it before. And there are a number of observations to make about this data.

The first is that these prices are set based on value, not costs. Taylor Swift charges $111.54 for a ticket to one of her performances because there is a perception among her fans that it has a value of $111. Similarly, the producers of a Cirque du Soleil traveling road show did not add up their expenses, and divide that number by the expected number of ticket purchasers to come up with a ticket price. Cirque du Soleil ticket prices are set based on value. So what is the value of a day at the air show? What will the public be willing to pay to see a multi-million dollar collection of unique and entertaining aircraft performing aerobatic maneuvers that take years to master? Certainly, more than $21.44.

Secondly, ticket prices tend to vary on how unique the opportunity is. Taylor Swift comes to your town once every year or two. Making a trip to Disney is not something that a family does several times each year. Whereas, every Major League Baseball (MLB) team plays 81 home games every year. National Hockey League and National Basketball Association games are less common than MLB games, but still much more common than National Football League games. Ticket prices for these events reflect their relative availability. And, of course, there’s nothing so common in the entertainment world as a movie screen; there are more than 40,000 in the U.S. alone and every one of them is available seven days a week, all year long. In contrast, most communities host an air show just once a year. As common as air shows might be to those of us working in the business, for the general public, they are comparatively rare events. This also suggests the need to increase ticket prices.

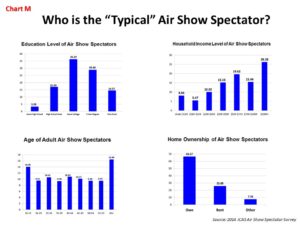

And who are the people to whom we are providing this entertainment bargain? One of the most highly-educated, affluent spectator bases in the event industry (see Chart M). Three years ago, after we released the results of our spectator survey, I got a call from the editor of a national marketing publication. He was sure there was a mistake in our survey results. I sent him the raw data and, days later, he called back, astonished. He said that we had one of the most affluent, desirable demographics he’d ever seen. He said we compared more closely with the audiences of golf and tennis than the football and NASCAR audiences he’d expected. So, we’re setting our ticket prices low for an audience that is perfectly able to pay much more.

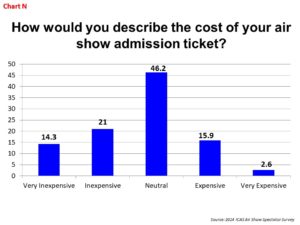

In fact, they’ve told us as much. In our biennial spectator survey, we ask this question: “How would you describe the cost of your air show admission ticket?” (Note: we ask this of all air show spectators participating in the survey, but we only use the responses for this question from the shows that actually charge an admission fee.) As you can see in Chart N, when we asked more than 2,000 spectators this question during the 2014 season, less than one in five (18.5%) said that the price was “expensive” or “very expensive.”

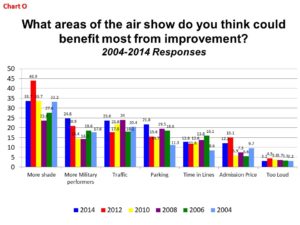

For several years, we’ve also asked spectators, “What areas of the air show do you think could benefit most from improvement?” And we’ve offered “admission price” as one of the multiple-choice options (see Chart O). The survey respondent was invited to check as many of the options as he/she would like. Historically, less than one in ten said that admission price was an area that could benefit from improvement. More recently (2012 and 2014), that percentage has been marginally higher. But we’ve never had as much as 15 percent of the tens of thousands of survey respondents indicate that our ticket prices are an area that could benefit from improvement. And, ironically, our industry’s concern about ticket price (an issue that our spectators are demonstrably and quantifiably NOT concerned about) has kept us from acquiring the resources needed to address issues that are a genuine concern for our spectators.

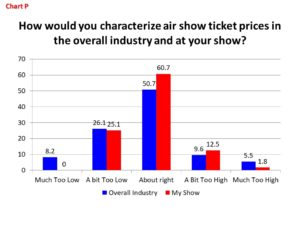

In our February survey, we asked event organizers how they would characterize ticket prices in the overall industry and, in a separate question, ticket prices for their own shows (see Chart P). As is typical for these kinds of questions, the majority said that ticket prices are “about right.” But, among those that expressed an opinion one way or another, a higher percentage said that prices are too low. Perhaps more interesting: those who believe overall prices are “much too low” don’t believe that the ticket prices of their shows are too low. Be sure not to miss this point: among those event organizers who recognize that ticket prices in the industry are too low, most believe that this is a problem for the “other guy.”

I’ve made this point – that air show industry ticket prices are too low and that increasing ticket prices is an easy and safe tactic to address cash shortages and long-term sustainability – in conversations with air show colleagues, in correspondence and at industry presentations for nearly two decades. Along the way, I’ve developed strong anecdotal evidence to support my position. Indeed, I have yet to hear of even a single show that raised its ticket price and saw any loss of revenue. In fact, in every conversation I’ve ever had on this topic, I have heard that, not only did the show that raised prices generate more revenue; they also saw an increase in attendance.

In this regard, an ongoing experiment at the Thunder Over Michigan show is important to consider. Thunder takes place near Detroit, an area that has been financially stressed during the last three decades. But air show director Kevin Walsh believed that ticket prices were too low. And he was eager to increase the cost of admission and overall ticket revenue so he could plow that additional money back into the show and invite a wider variety and larger number of interesting and exotic aircraft to participate in his event. So, he conducted a multi-year experiment. The show raised ticket prices by $5 each year, looking for the price at which the general public finally said, “That’s too much,” and overall attendance started to decrease. They started at $25 and raised it to $30. Both overall ticket revenue and attendance increased. So they raised the price to $35. Same result. I was at the show last summer when ticket prices were up to $40. The show had record-breaking attendance figures and, at $40 per ticket, overall ticket revenue was up. Thunder Over Michigan has still not found the price at which attendance begins to decrease.

Now Thunder Over Michigan didn’t introduce these price increases carelessly or casually. As part of this experiment, they made tickets available at last year’s prices if the spectator bought the tickets early. For instance, in the year that Thunder increased prices from $35 to $40, they sent out promotional materials encouraging fans to buy their tickets early at the old $35 price. But, along the way, they demonstrated that – even in a community that has been as economically challenged as southeast Michigan — fans understand that attending a world-class aerial entertainment event comes at a cost.

Obviously, each show’s experience will differ based on details and circumstances, but I will repeat what I said earlier: In the nearly 19 years that I’ve been asking air show event organizers about their experience with ticket price increases (and, as some of you know, I ask this question quite a lot), not a single one has ever told me that increasing ticket prices resulted in a drop in attendance. Not a single one.

An Option that Deserves Your Consideration

The argument for a widespread ticket price increase in our business is overwhelming.

- Clearly, the air show community needs the infusion of revenue that would accompany an industry-wide increase in ticket prices.

- Our prices are dramatically lower than other entertainment venues despite the fact that we offer what is, arguably, the most unique form of entertainment in the world.

- The people who attend our events are just as familiar as we are with what it costs to attend a rock concert, amusement park, or sporting event. There may even be a reasonable argument that the low admission fees are creating the impression among prospective ticket buyers that our events do not have the value that we all know that they have.

- They have all but told us that they would expect higher ticket prices at our events and their demographic profile makes it clear that they can afford higher prices.

- As an industry, we understand that our ticket prices are too low, even if we think that it’s mostly a problem for “the other guy.”

- And both anecdotal and statistical evidence tells us that there is little financial risk associated with increasing air show ticket prices.

Discussions on ticket price increases sometimes become emotional. “We need to keep it affordable,” or “We have a responsibility to the community.” But ticket price increases are a business decision. And decisions about possible increases should be made dispassionately and objectively, using all of the information available.

If your show is considering a ticket price increase, but you’re a bit nervous about it, conduct an experiment. Raise your prices a small amount and monitor for adverse effects. Or raise a particular kind of ticket more dramatically and see if there are negative repercussions. If the experiments go well, implement larger price increases or apply them more broadly. Every bit of evidence available suggests that there will not be a problem and that the only impact you’ll see is increased ticket revenue.

The air show community has suffered through chronic cash shortages for years. Is it possible that, with a little courage and in a single stroke, our industry can address this longstanding problem? With so many people working so hard and over such a long period of time, this simple, elegant solution – which can be implemented almost immediately – deserves your attention and consideration.