Air show announcers come in all shapes, sizes, genders and price ranges. They are essential to both the entertainment and safety of fans. Fees can range from as low as free or a few hundred dollars, up to several thousand dollars depending on popularity and proven level of experience. And like most performers in the air show business, when it comes to announcers you usually get what you pay for. Said another way, a lame performer might mess up ten minutes of your show, but a poor announcer could ruin your entire weekend.

For a number of years, there was a tendency in this business — especially for first-time shows — to bring in a local radio voice to narrate a show, but few of them had any aviation experience and even fewer had air show experience. Organizers thought all the announcer had to do was read the scripts given them by performers, but soon discovered they didn’t know how to use a public address (PA) system effectively, didn’t understand what they were reading, and often didn’t know the difference between a Pitts and an Edge. Consequently, the shows suffered. But, from that cadre of local broadcast talent has emerged some of the industry’s top announcers…people with all the requisite skills on the microphone and the knowledge of air shows and aviation that our industry needs.

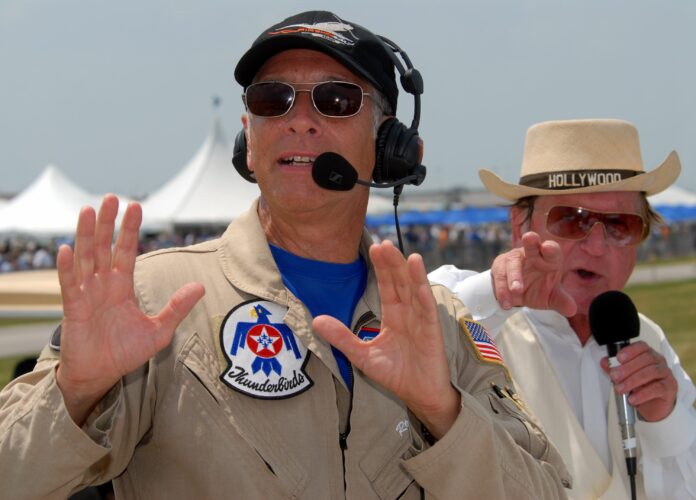

Announcer Rob Reider comes from a live television background that has served him well, because an announcer must fulfill multiple roles simultaneously. “A good announcer must entertain, inspire, educate and inform, all at the same time. In live television — just as in live radio — the pressure is always on to keep things moving,” he said. His experience has been a benefit as he narrates the acts, fills the gaps between acts, covers when there are delays and makes sure the sponsors get the credit they deserve. “I can’t fail the sponsors because they are the ones who are paying for it,” he said.

He says he received his share of criticism from air show fans when he first started. “When I first got started in the early 90s, I was stopped by fans who told me I was too technical. I was reminded that most people don’t know a fighter from a bomber and they were right. I now may weave in some history about an act or an airplane, but I’m sure not going to talk about the dihedral of the Corsair wing,” Reider said.

One of the biggest challenges for any announcer is to keep the fans engaged, because — no matter how skilled an announcer is — there is a point where narration becomes noise and people simply tune the announcer out. Most narrators respond with intermittent periods of quiet, insertion of music, or simply changing voice inflections. “I use my voice to build excitement for a high energy performer, and soften my voice for something like a glider act. I try to match my voice to what people are seeing,” said Reider. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t because, in reality, someone is always tuning out somewhere. “In the end, people paid their money to be there and it’s up to them to decide if and when they want to listen,” he said.

Shows that can afford it will hire more than one announcer. Two voices often keep fans’ attention better than a single voice. “My model is still Al Michaels and Chris Collingsworth doing football play-by-play with a third person down on the field. They bounce off each other well and the TV audience enjoys it,” Reider said.

Another broadcaster turned air show announcer is Ric Peterson. “An announcer is a ringmaster. He’s the conduit between the performers, the advertisers and the audience and he has to be able to change hats quickly,” he said.

Peterson believes an accomplished announcer is someone who understands the business of entertainment, possesses the skills and experience to use the PA system correctly, and relays information to the crowd about what they are seeing, and why they are seeing it. It’s no simple task. “Prepare, prepare, prepare,” he said.

An old adage says: “Don’t speak unless you can improve the silence.” And announcer Roy Hafeli was taught that early in his career. “Some acts need a strong voice to go with them, but others don’t. And we have to strike that balance,” he said. A key example is warbird acts. “I try to do my narration of warbirds while they are in their turns because the fans want to hear the engines,” he said. Some fans consider it a cardinal sin to talk, for instance, when a P-51 flies by.

For Hafeli, the key attributes any show should look for when hiring an announcer are experience, style, and background. “Shows need to make sure their narrator is a good fit for the show and that they have the background to meet the show’s needs,” he said.

Not all announcers have a broadcast background, however. Veteran announcer Danny Clisham was a commercial pilot when he narrated his first air show. “There were so many people out there announcing shows who didn’t know what they were doing. I knew I could do a better job,” he said. “The hallmark of a good announcer is someone who puts his ego on the shelf and recognizes it’s not about him or her…it’s about the show, the audience and the sponsors. On the ground or in the air, it’s the show that is the star,” he said.

For Clisham, it’s all about expressing the joy of aviation. “It’s the joy of being outside, being surrounded by family, and entertaining fans, whether they are small children, teenagers or grandparents,” he said. And because of the family nature of air shows, Clisham says there is no place at air shows for off-color jokes or anything else that would embarrass fans.

Like any other profession, aviation has its own jargon the public does not always understand and it must be avoided as much as possible. “A good announcer never talks above the crowd. We talk to them in a way that they can understand and become a part of it. Don’t demean them and don’t make them feel dumb,” Clisham says.

Announcers have to be familiar enough with each performer’s routine to handle variances that sometimes occur and to cover them seamlessly. Often, pilots will alter their routine due to a variety of issues and the announcer is usually the only person on the ground who notices because he has the performer’s sequence in front of him. And when a performer does not have the numbers to complete a Cuban Eight, for example, it’s the announcer who smoothly transitions into the setup for the next maneuver without calling attention to the change.

While announcers have to be prepared to entertain, they also have to be prepared for tragedy, which means having the maturity and experience to shift immediately into a take-charge mode to keep fans calm and safe. “You have to shift from being an entertainer to a human kindness counselor, using your voice to provide comfort,” he said.

Clisham was the lead announcer at the Reno Air Races on September 16, 2011, when the P-51 Galloping Ghost suffered a catastrophic mechanical failure and crashed into the apron in front of the grandstands and box seats. The pilot and ten people on the ground were killed and another 69 people were injured, some critically. It was one of the most horrific accidents ever at an American air event. Parts and pieces of the aircraft were flying in every direction, including toward the announcing stand, but Clisham stood fast and was credited with keeping the crowd calm so first responders could do their jobs. “A good announcer will be mentally prepared for almost any type of accident and will have gone over it in his mind ahead of time. I had to deliver calm instructions to the crowd, soothe them, and give them direction on how to respond,” he said.

Most narrators have what they call their “last page” which is the last page in their binder that reminds them what they should be saying when an accident occurs. By making it the last page, the announcer doesn’t have to fumble with pages to find it.

Ric Peterson has a last page, but he says he rehearses in his mind how he would handle different scenarios so that he doesn’t get slowed down in his response.

One of the biggest issues for an announcer is knowing who to take direction from when an incident occurs. Some announcers make sure they get copies of an air show’s disaster plan well ahead of time to understand how first responders will work.

When Rob Reider began narrating, he contacted as many experienced announcers he could reach for guidance on how to react to problems. “I wrote down everything they said, memorized what they said, practiced what I would say out loud, and compiled their comments into my last page,” he said. Reider says he has learned to compartmentalize when an accident happens. “Performers are friends, but — when tragedy strikes — I can’t let emotion take over. I have to remain in control so that I can do my job,” he said.

Former aerobatic performer and coach Wayne Handley says an announcer should be the first person hired by a show. “The announcer is so important because he is the glue that holds the air show together and makes the link between the performers and the audience,” he says. Ric Peterson agrees and believes the next individuals hired should be the air boss and sound system. “Because of the safety aspect the air show industry is unique, and the narrator, air boss and sound system personnel have a shared responsibility and must work together seamlessly,” Peterson said.

Longtime air boss Ralph Royce says the announcer has a responsibility to the crowd to keep them updated on everything that happens in front of the show line, as well as behind the show line. If an accident occurs in front of the crowd, the air boss has his hands full dealing with the emergency and relies on the announcer to keep the crowd informed and under control. “If there is an accident, we can’t hide from it. We have to be transparent with the audience. I have to focus on what happened and what is going to happen on the field. I can’t be distracted by audience issues and it’s up to the announcer to handle that,” Royce said.

Air boss Wayne Boggs agrees. “A good announcer is worth his weight in gold. When things go south, for whatever reason, it’s the announcer who is going to make it transparent to the crowd. I have to make sure I give the announcer the information he needs and nothing he doesn’t need,” Boggs said.

Air bosses typically hold meetings with first responders on Thursdays before a show to go over the procedures for air space handoff, authority over responders, etc. And most air bosses ask narrators to attend. “I want the announcer there because it helps define the flow of information,” Boggs said.

Ric Peterson feels it is the announcer’s responsibility to understand each show’s safety plan. “I take a long, hard look, especially at the things I’m responsible for…crowd control, traffic, closure of the show, and I look to make sure the traffic plan is in place before making any announcement, especially if we end the show early and everyone leaves at one time,” he said.

Boggs and Royce agree that the overall professionalism of announcers has improved markedly over where it was twenty or thirty years ago. But Royce said he’s concerned about the future. “I worry about announcers just like I worry about air bosses. We don’t have enough new, young talent coming into our industry who understand air shows, who understand this business, and are willing to do the job,” Royce said.

Excellent beta from the Business’ BEST. AND THANK YOU MIKE,, DANNY, ROB, RIC, AND MATT AND ALL OF THE MANY Announcers and narrators who continue to inspire and mentor the future of our industry.

Comments are closed.